Robotic Oceanographic Surface Sampler

Oregon State University

College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences

Ocean Mixing Group

Summary

Timeline

Started

Joined ROSS

Setup & Ocean Trials

Petersburg, AK

Glacier Deployment #1

LeConte Glacier, AK

Glacier Deployment #2

LeConte Glacier, AK

Scientific Paper Published

The Oceanographic Society

Finished

Left ROSS

Key Takeaways

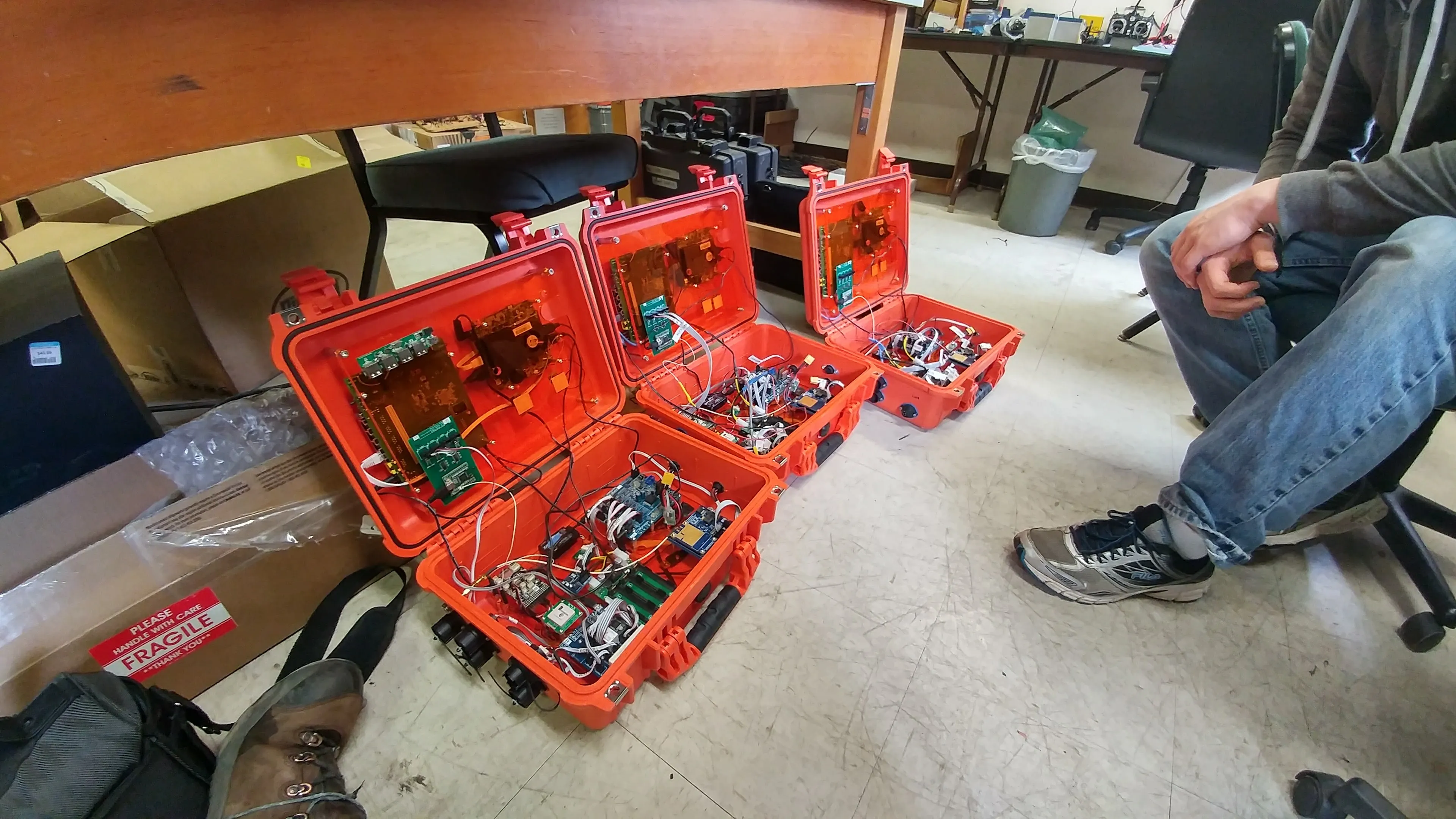

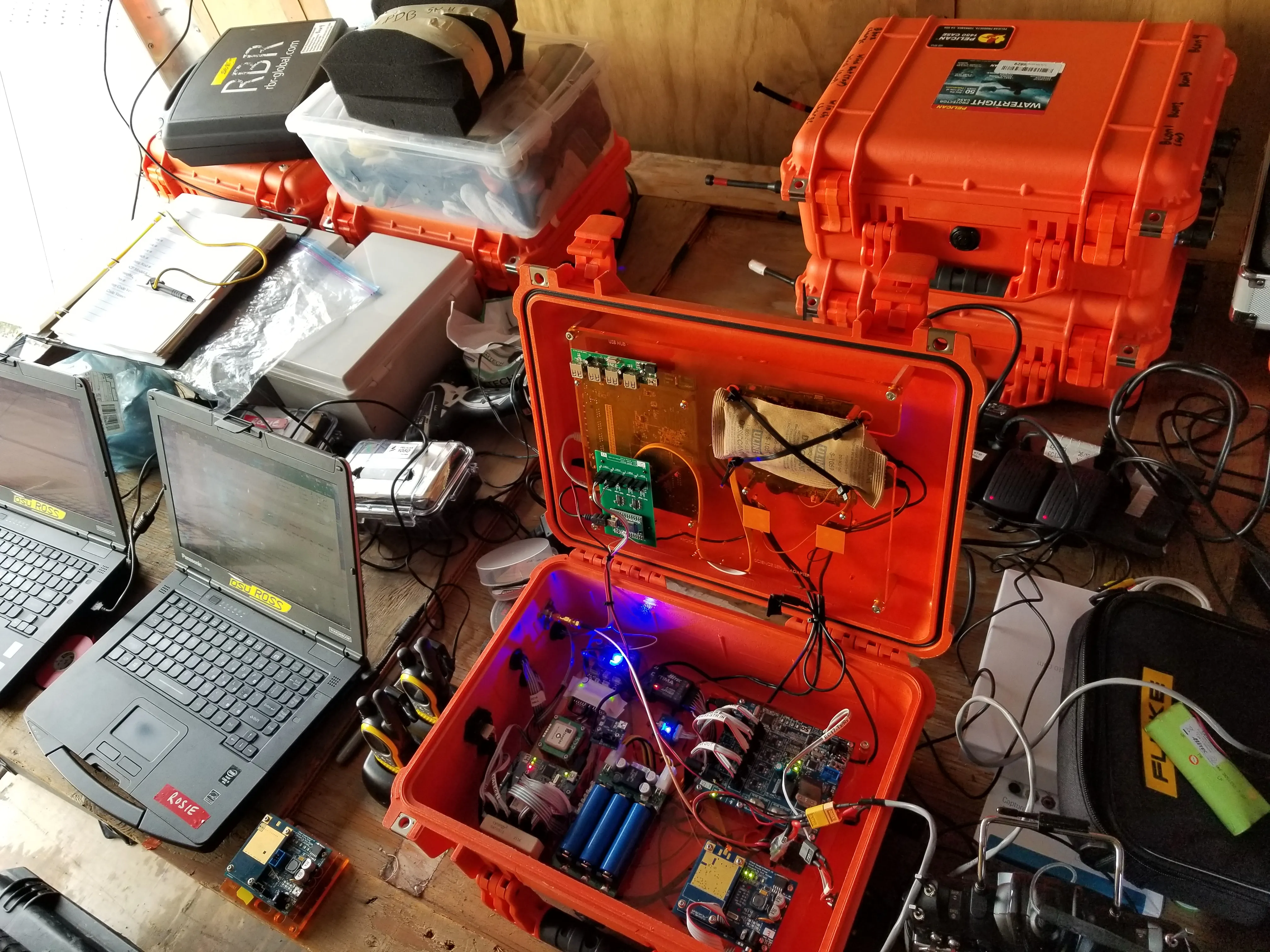

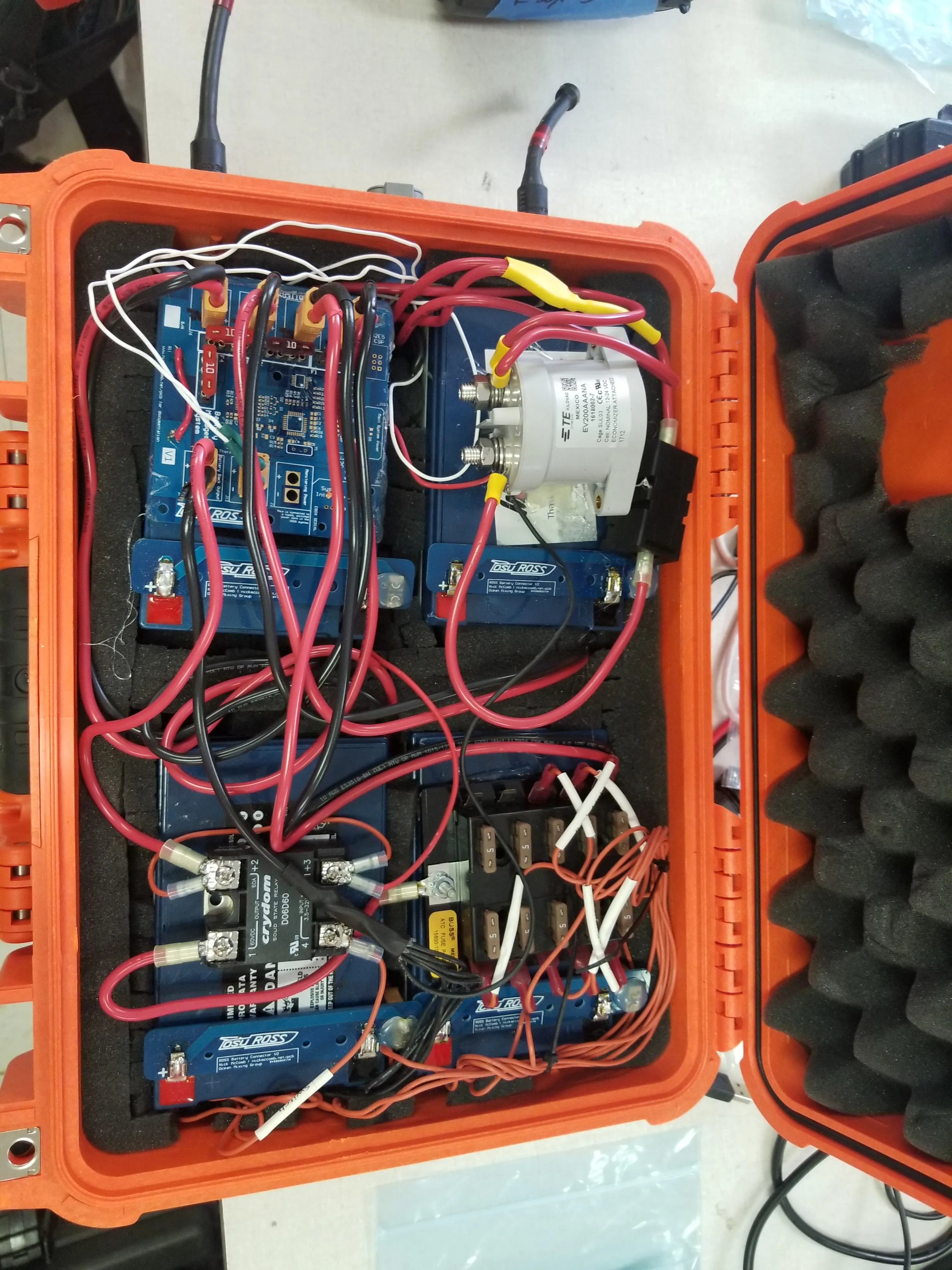

- Hand assembled and validated dozens of custom PCBs, wiring harnesses, and electronics boxes

PCBs

Printed circuit boards

- Wrote, debugged, and assisted with development of embedded firmware

- Accompanied the team on two deployments to the LeConte glacier in Alaska to gather ice-water melt and mixing data

Relevant Skills

Electrical

- Schematic & PCB Design

- Altium Designer

- PCB Assembly & Rework

- Handheld Soldering

- Handheld Hot-Air Reflow

- Oven Reflow

- Electrical Diagnostics

- Multimeters

- Oscilloscopes

- Logic Analyzers

- Harnessing Fabrication

- DC Power & Signal

- Low Frequency RF (<1GHz)

- Waterproofing

- Simulation

- LTspice

Software & Environments

- Git

- Programming

- Python 2/3

- Bash Shell Scripting

- Low-Level Embedded C/C++ (Atmel Studio)

- High-Level Embedded C/C++ (Arduino/Teensy)

- Matlab

- Operating Systems

- Linux

- Ubuntu

- Raspbian

- Microsoft Windows

- Linux

Details

ROSS Overview

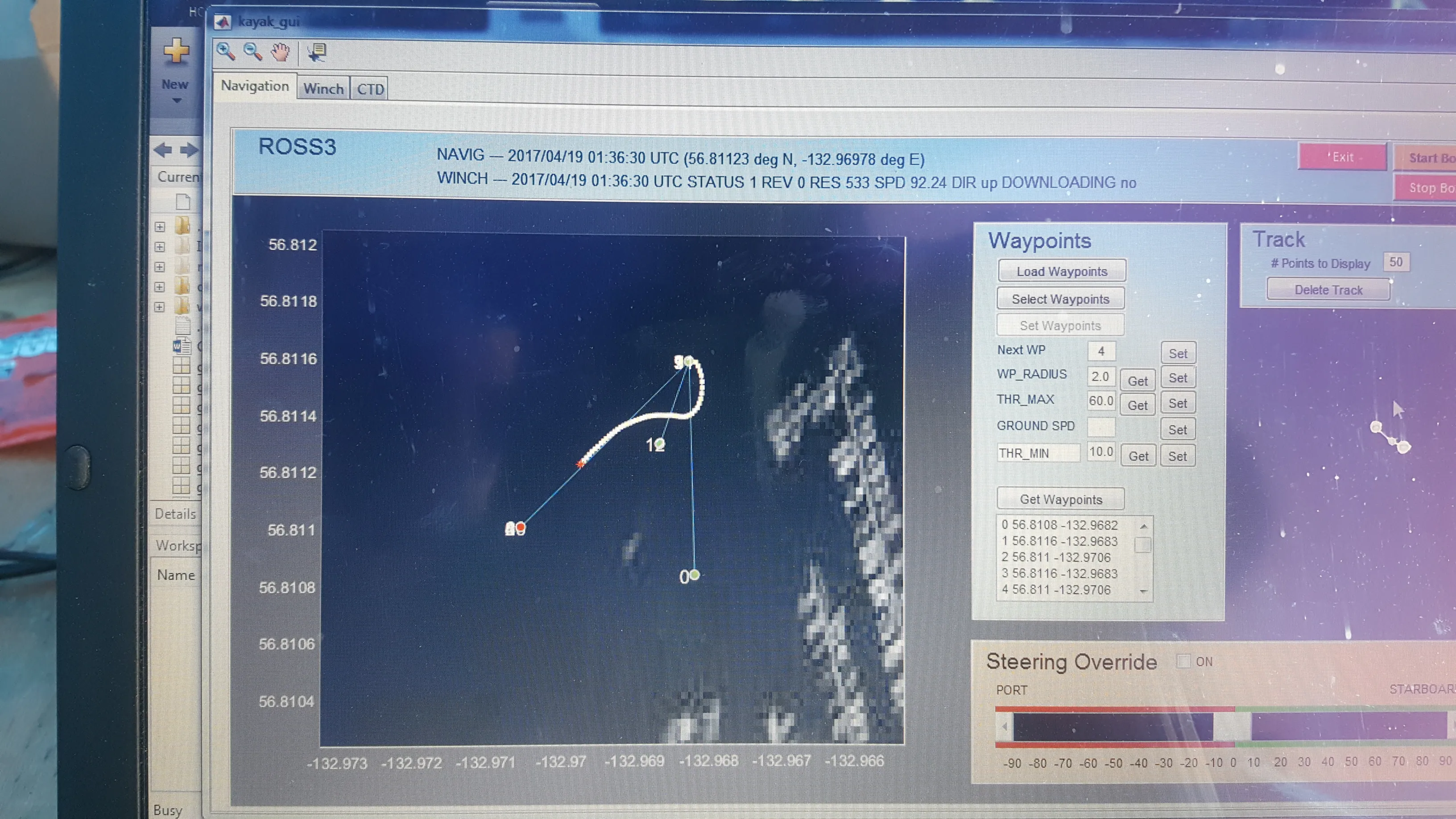

ROSS was a gasoline-powered water-sampling robotics platform built

around a Mokai jet-drive kayak. It's purpose was to continuously, and

often autonomously, gather water data over extremely long distances

and/or in locations where human-safety concerns would make gathering

it manually too risky. There were a variety of sensors it could be

outfitted with depending on the needs of the exact research project

and destination, but some common ones were an ADCP for gathering 3D water current vector data, a CTD for measuring water conductivity/temperature/depth, and a high-precision

GPS for generating meaningful 3D plots of the sensor data. These kayaks

have been deployed to places like the Indian/Pacific Ocean mixing line,

and along the active LeConte glacier terminus in Alaska, gathering novel

data on how vastly different bodies of water act when mixing.

ADCP

Acoustic doppler current profiler

CTD

Conductivity, temperature, and depth sensor

In its original configuration, the Mokai kayak's throttle and steering

were already drive-by-wire, which made it an excellent starting point

for automating. It was also designed for easy transport, breaking down

into three major compartments that could easily fit in the back of a

short-bed pickup. For our custom hulls, Mokai also thickened the

plastic significantly and provided a bare minimum of electronics. This

barebones platform was then modified by our team to include a

storm-surge-rated intake and exhaust for the engine, a keel to improve

rough sea stability, a large alternator, and a plethora of mount

points the electronics, batteries, fuel, sensors, and radios.

In terms of the electronics and software for this project, the kayak

itself was centered around a Pixhawk flight controller flashed with a

modified Rover variant (this was before a dedicated boat option

existed). One pelican-case electronics box housed this controller, a

small NUC with UPS, wifi router, radio control receiver, satellite modem, and quite a

few custom PCBs for interfacing with external

electronics and implementing glue logic/safety overrides. A second box housed

nothing but sealed lead-acid batteries, which were charged by the alternator

on later revisions of the platform. The PC ran a custom python script, which

interfaced with a Matlab GUI over a remote radio link. The kayak could also

be overridden with an FrSky RC controller, when at close range, and additionally

allowed for direct control without the PC needing to be in-the-loop. To

see some of the custom hardware inside of these boxes, check out Nick McComb's

design pages for them

here! For even more context on ROSS, and history from before I joined the

project, check out his summary page.

NUC

A small and low-power computer made by Intel

UPS

Uninterruptible power supply

PCBs

Printed circuit boards

My Experience

I first started on this project by doing what I thought was a one-off

help session for Nick, working on an issue he was having getting

ROSS's engine to start and shut down properly. I had more experience

with engines, and engine control, so I quickly realized that a beefier

and high-voltage-rated relay was needed to avoid arc-welding the

contacts closed during shutdown. He rolled out a new board revision with those changes and it was the final version used for the rest of ROSS's

lifetime. This little taste of the project, and some wishful prodding from

Nick, was enough for me to join the team part-time.

While the original plan for me was to re-write the GUI for ROSS in Python using Qt, it turns out they needed my help on the

electrical and firmware side more than anything, so most of my time at the

lab was focused on that. I hand-assembled so many of Nick's circuit boards

at this lab that I still can pick his out of a lot from design aesthetic

alone! I also helped with plenty of wiring harness builds, electrical box

fabrication, embedded firmware development, and of course, plenty of electrical

and software debugging. One thing that this project taught me very quickly

was how difficult it was to make reliable hardware in a high vibration,

electrically noisy, and salt-laden environments. The number of PCBs we went

through, alongside wiring harnesses, was pretty incredible considering the

lengths we went to in order to protect them.

GUI

Graphical user interface

A very unique aspect of this team/project, and a large part of why I

was drawn to it, was that it was about as hands-on as you could

possibly get. Doubly so for an undergraduate student! Not only did I

get to design and repair a real robot, but it was actually being used

for proper scientific research! We would regularly go to Newport, OR

for testing and have to make crazy additions and repairs on the fly.

This got even more extreme during my deployments to the LeConte glacier, as you had to get creative and fix things with what you had on-hand

due to how remote we were. These are experiences that graduate

students rarely even get to have, so I'm extremely thankful and fond

of the time I spent here. Huge shout out to Nick, again, who made it possible in the first place! Also be sure to

check out the scientific paper on this project below!